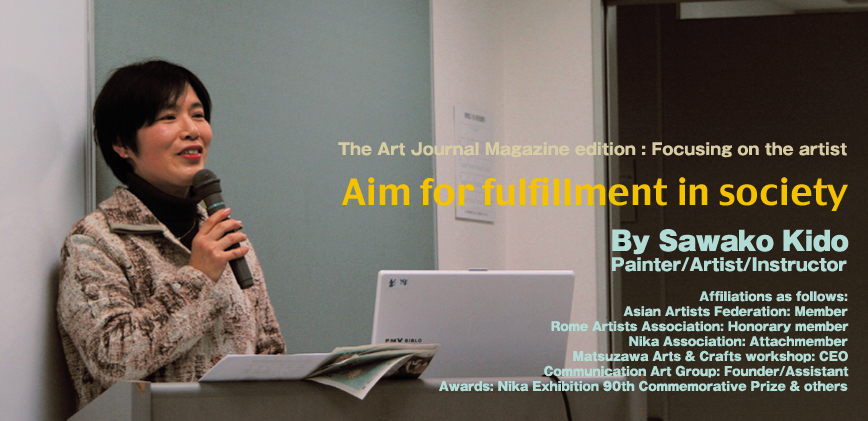

Sawako Kido is the creator of the acclaimed aquifer series of paintings – an abstract vision of the origins of the innermost depths of the human psyche. As an art instructor, she has played an instrumental role in successfully mentoring students with severe mental challenges. At her home in Fukuoka, Japan, she lectures us on her art activities and her experiences mentoring students.

Lecture Series: Bringing to Fruition our Latent Abilities

Date: Feb. 22nd, 23rd (Sat/ Sun) 2009.

Place: Madokapia Cultural Center, Onojo City Fukuoka Prefecture Japan.

Topic: Kosuke Ota: A Portrait on the path of the Artist

Speaker: Sawako Kido

Hello,

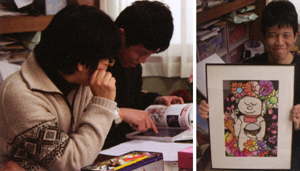

I’m Sawako Kido, founder of the Matsuzawa Art workshop. It’s my pleasure to be here today to give you a first-hand account on the path taken by Kosuke Ota as an Artist.

Today I’ll talk about art as a vital form of expression for the challenged. Among mentally challenged individuals, there are some more skilled at oral expression and others less so endowed. In the latter case expressing ones ideas verbally can be labor intensive. I believe that such individuals instead often find their niche to self-expression through music or art. At my workshop in Onojo City, I use a strategy of communicating through art.

I use painting, clay working, paper cut out techniques and other such media to foster creativity and imaginative works. Kosuke’s main means of expression has been through the creation of paintings. His mother has noted that his panic attacks have considerably declined since he has started painting. This is an inverse relation. His increased ability to express his inner most ideas and feelings have brought calm and inner peace and decreased his penchant to panic. In life we sometimes have persistent thoughts or we are vexed by negative experiences. We have this deep seated desire to elucidate on how we feel and extricate those ideas and emotions from our psyche; to purge them from our system and make them concrete and clear. An effective way of doing this is to express those ideas or feelings into art. We draw, sing, and compose, healing our minds and returning to homeostasis in daily life. I therefore believe there is ample room for using art as a strategy for communication in our lives.

Autism

Kosuke has astonishing memory skills. He had, for instance, completely memorized our annual class schedule. Here I am trying to remember if we have a class and I find myself relying on him to let me know our class days. Another autistic student in the class has memorized the order of the books on my bookshelf…all of them! One day after I was reading from my library, pulling books out and strewing them all over the floor, I put them back on the book shelf randomly without thinking. This student promptly reminded me which books were out of order, misplaced or missing from the bookshelf. That’s just one example of the kind of ordered, photographic memory some autistic students possess. As a result of these experiences I came to the conclusion that intellectual ability and memory recall may be distinct from one another. Often the autistic student’s lucidity of memory can be detrimental. Negative experiences and thoughts seem to stay fresh and seem to be all the harder for these students to let go of, especially if those memories are strong or fixed.

Most people normally have an ability to sift through and let go of painful memories.

Often with the autistic, rather than such memories just fading away with time, some catalyst in their daily life may bring back those thoughts, sparking off a panic attack.

This is an important reason why I sense we need a better understanding of the particular needs of the mentally challenged.

Many people are surprised to learn that from the start Kosuke Ota, an individual with heavy autism, showed total disinterest in learning art. Furthermore he was unable to sit still for more than 5 minutes at a time, nor adequately able to communicate orally.

My approach for teaching him evolved in the following manner:

I relied on trial and error as a lesson strategy

I learned to trust my instincts and be patient.

I recognized the importance of practice through constant repetition and review.

During the first three years I kept repeating the basics.

I began to observe clear signs of improvement after five years.

I used his interests, for instance the “Power Rangers” action figures, as a catalyst for teaching him to enjoy art.

Kosuke first came to my workshop when he was in the fifth grade. At the time he was unable to sit still in my class for much less than even five minutes. Furthermore he was barely able to communicate with me orally. He consistently kept walking and milling around for the duration of the lesson.

For instance, I would tell him, “Do you want to do something today?” To which he would just repeat back to me in parrot-like fashion “Do you want to do something today?” Every single thing I said would just be repeated back to me in echolalia. I decided to invite his mom to look in on the lesson, and pondered on how difficult it would be for her to watch as these strange antics played out in front of her, but I was surprised at her reaction. Rather than taking him home, she pleaded with me to persist and let him continue participating in the class. With a fair amount of reticence I grudgingly agreed. At this point I have to just say honestly, that I had absolutely no confidence things could ever work out successfully given the circumstances. First off, I thought, I’m an art instructor. I’m not a social worker and I’m not certified to do that sort of work. Furthermore, I’ve had absolutely no experience working with challenged students whatsoever. I honestly sat down at loss with myself and in despair for a good week, trying to think how in the world I was going to accomplish teaching him art? Regardless, I was moved by the look of sincerity in Kosuke’s Mother’s eyes at the time, and like someone groping in the dark, without manual or guidebook, I decided to see what it was that could be done. As a starting point, I asked his mother to inform me on his interests; to simply tell me the kinds of things he liked, and on that note we started the art lessons.

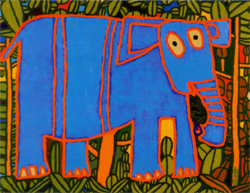

Kosuke was really captivated by the Power Ranger TV show and action figures. He loved the color schemes of the character’s uniforms, especially the reds, whites, yellows, blues and greens. He also liked playing with clay at home. So I decided to combine those two interests. I asked him if he’d like to make the Power Ranger action figures out of paper clay. He’d never painted on paper clay before (neither had I for that matter). So half jokingly I said “when the paper clay has dried, how about we paint it red, yellow and blue?” He answered me with a simple “yes”. So in this way, for the first time, I succeeded in getting him to use the paints and other art materials at hand. This was the first time I felt the possibility of being able to guide him into participating in the activities at the workshop.

Drawing from sight

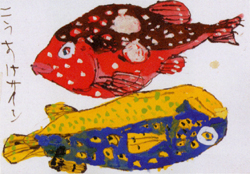

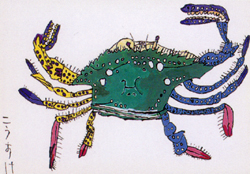

For the first three years Kosuke could never draw from sight. I would place an orange on the table but he couldn’t draw it. Many people look at his paintings nowadays and often ask me whether he was a natural at art. We often hear about the savant autistic’s genius capability. So that means he was talented from the outset, right? This couldn’t be further from the truth. Actually, it was exactly the opposite. At the outset, he was the least able to draw of all students in the workshop.

To deal in such cases where students were unable to do a freehand drawing of an inanimate object I had the following strategy: I would ask the student to first draw the outline of the object with a thick brush in order to reinforce necessary drawing skills. Persons unaccustomed to drawing will usually draw thin, weak lines when asked to. So this was the start…and the goal, drawing outlines of things in strong thick lines from start to finish. As with all other students, I made him draw strong, straight, thick lines in color pencil. For Kosuke, who understands visual cues better than words, a picture is worth a thousand words. At the time, Kosuke seemed virtually unable to follow oral instructions. However, if you drew something down on paper he understood. So, I would draw to show him what I wanted him to do, and in this way too, drawing became the requisite tool for communication of instructions.

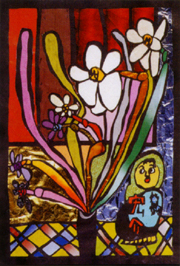

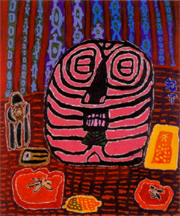

In the spaces in between the lines that Kosuke had drawn by color pencil, I told him to “color this in, in red. OK. Next over here” and I let him choose whatever color he liked to fill in between the lines. Large spaces, small spaces, he colored them all in, in his own unique way.

Then after practicing drawing lines, we started practicing drawing circles. I told Kosuke, “Anyway, just keep drawing and go round and round and let’s just draw all kinds of circles, even scribbles are OK. Keep on drawing round and round, then, color in all the circles you’ve drawn.” And then right where two circles intersected and he mixed red and blue…purple appeared. Then we did the same with paints. Where two colors intersected, a new, different hue of color appeared and … it was interesting!